When news first broke about the God Bless America Bible (GBAB) and its $60 price tag, of course I rushed to tell my wife. As

said in a recent post, it is “the Bible America deserves” and I wanted to talk about all the ways that was true.I mean… Maybe that was the only true thing. Maybe everything had been said that needed to be said, but hell, why not say it again? “This is the Bible America deserves!”

“Well duh,” Jenna said, “what else is new?” She shrugged and went on with her life.

I was, you’ll understand, put out. I wanted to moan about this. It’s a very moan-worthy piece of news. Why did I ever get married except to harmonize my complaint with the voice of another? But she just treated it as par for the course, as predictably despicable, and therefore not worth her outrage. So what if an artifact now exists that fully and parodically enshrines American Christianity’s selling-out to partisan politics of the most juvenile kind? Further talking about it or dissecting the lurid website (which is full of way-past-its-time marketing copy, by the way) is unlikely to yield any new insights into that most pressing problem.

There is not, in other words, really anything here left to interpret. And that’s actually a very strange circumstance for us to be in–especially evangelical Christians, whose fraught relationship with the mysteries of the Bible tends to make us, if not always good readers, particularly aggressive interpreters of media and culture. The Satanic panic of the 80s and 90s is one example; even in the mid aughts, in my LCMS high school, my band teacher would cancel class to play videos about the dangers of subliminal and backmasked messages in rock music. (It’s fun to smoke marijuana, eh?)

This is the exact video my teacher used to show. Yes, it’s 3 hours long, we cancelled whole weeks of class for this.

We also had less crazy outlets like Focus on the Family’s Plugged In magazine which, through the early 2000s, reviewed music and movies for “Pro-Social” and “Objectionable” content and advised parents whether to let their teens consume certain media on those grounds. These reviews weren’t about subliminal messages, but they did teach me the evergreen skill of close reading (and the less evergreen skill of sorting what I read into rigid moral boxes. Credit where it's due, though, if I have anything insightful to say about Beyoncé, it’s because Evangelical journalism taught me everything required interpretation).1

And this kind of cultural engagement actually made sense for the times. As Penn State English professor Jeffrey Nealon describes it, media and culture were heavily textualized in the 80s and 90s. Meaning was a hot commodity, interpretation and “critique” the pinnacles of cultural engagement. (You might even call it “culture war”...?) Ironically, the folks best positioned to do this kind of work were postmodern academics and evangelical Christians who (sometimes literally, depending on what your Sunday school looked like) ate hermeneutics for breakfast.

But things have changed, Nealon says. There’s a lot less meaning to suss out of cultural and political expressions which are now more about spectacle and the immediate creation of feelings. Everything is on the surface. “Vibes” resist analysis by virtue of their shallowness. Capitalist cynicism no longer bothers to file its teeth. The GBAB is a perfect example; those whom the product is made for will most certainly buy it while those of us who are going to be scandalized by it were already as scandalized as we could be 8 years ago.

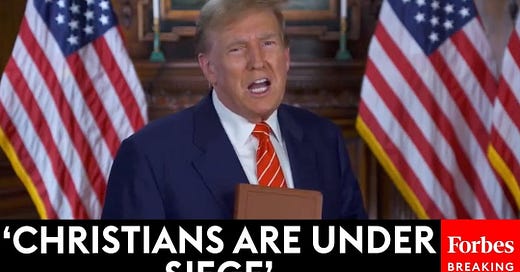

Which inches me towards a concern I have with the continued discourse around Christian nationalism qua Donald Trump’s religiously-backed takeover of politics. Back in 2016 we asked how the Republican Party could, largely pivoting on the wheel of American evangelical opinion, turn a one-eighty from its moral outrage over Trump to a full-on endorsement and even cultic fanaticism. We got explanations–lots of them, from very good scholars, each filling in a piece of the whole picture.

And yet the explanations seem to keep coming. The commentary won’t stop, not even over something as (let’s be real) banal as the GBAB. And it’s my feeling at least that we’re learning very little from this ongoing commentary that we didn’t already know. Those who eruditely explained the ascendancy of Donald Trump and white Christian nationalism now describe its ongoing effects–but these are not the same things.

I do think we’re still mystified and so unsatisfied with the explanations of what happened. Maybe we should be. Maybe the story is still only 70% told, and we’re looking for the other 30% to help us know what, finally and conclusively, to do about it. But if that 30% isn’t forthcoming, we’re not going to find it in GBAB commercials or between the lines of Trump’s Truth Social posts. These aren’t “evidence” to be rifled through; they are part of a spectacle demanding we play by its rules.

I don’t mean one shouldn’t read or write about these things. There’s still value in paying sustained attention even to our most cringe-worthy steps on the road to the November election.

, for example, shows how these bits of pageantry add up to a strategy for winning over a religious voter base in bad faith. This is something to take very seriously:But the thing about spectacle is that it craves attention. “Any publicity is good publicity,” we’ve heard, and Trump seems to take that to heart. And why wouldn’t he, when our media cycle enables it? Cultural commentary aims to have the fastest and most blisteringly current interpretation possible. We know this as having a “hot take.” But in our media-saturated world, speed often signals and bestows legitimacy. If a topic or event is generating hot takes, that becomes proof of its power.2

Trump’s entire strategy involves generating hot take after hot take, keeping all eyes on him and therefore keeping his power secure. Not only does he live rent-free in the American mind, his looming presence blinds us to subtler political movements–or even to what’s going on in our own backyards.

The GBAB stunt is more of the same. It is only a symptom of things we already know, a distraction from other things that are more important. It takes advantage of how fun it can be to get mad at stupid things. But it also keeps our butts on our couches, neglecting our porous and vulnerable souls. Nealon describes ours as an economy not of “goods or services” but of “the thrills of winning, the aches of losing, the awe of the spectacle,” in which “you don’t so much consume goods as you have experiences where [you] can be intensified, bent, retooled” (27-31). You are what’s at stake here.

So we can’t afford to play by the rules of the spectacle. Under its reign, our continued obsession with meaning works against us and “critique” no longer does what we think it does; it quickly reduces to mere content creation and feeds the very machine we wish to halt. At worst, it is mere “moaning” which, according to commentator Natalie Wynn, is more politically insidious than we might think:

[I’m reminded of Fyodor] Dostoevsky's second-most horrible protagonist: “Even in toothache there is enjoyment, in that case, of course, people are not spiteful in silence, but moan; but they are not candid moans, they are malignant moans, and the malignancy is the whole point.” … Part of the satisfaction of moaning is inflicting your pain on other people [in a way that] masquerades as a political agenda. [It] outwardly appears like moral or political critique, but…on examination is mainly just a resentful moan. [Resentful people] don't want victory, they don't want power, they want to endlessly "critique" power. Because for them, "critique" is an important psychological defense against feeling impotent.

What else was the “cultural criticism” of the Moral Majority, after all, except for a “resentful moan”? We can still fall into that trap from other side of the aisle.

Again, I’m not trying to criticize anyone who’s written on the GBAB in the last 2 weeks. I am noting, though, that Christians have become very comfortable with “critique” as a form of cultural engagement, and right now, especially when the world needs us at our critical best, we might also want to attend to the limits of critique. If anything I’m writing to remind myself of how vulnerable I am to the trap of mistaking “moaning” for making a difference.

… But then, what do we do instead?

“The answer is surprising,” writes the late Biblical scholar J.P.M. Walsh, who might have identified our culture of spectacle among the Biblical “Principalities and Powers”—the “structural and societal givens” which “tell our story” and only grow stronger when we try to defy them (or moan about them):

[The answer] is surprising to us and it was surprising to [the first Christians] (1 Cor. 2:8; Eph. 3:9-10). The way to shake loose of the determinism of the Principalities and Powers is not going against them, or getting around them, but, so to speak, letting them do their worst. Let them do their worst and you will show them up for what they are. Let them rage and have their head and enforce their will and assert their absolute claims, and the true limits, the pitiable emptiness, of their supposed absoluteness will appear for all to see. They will be discredited. Confounded, they will find themselves a laughingstock. They will have to accept their proper place in the scheme of things, and acknowledge [they are] not the whole story… The cross embodies this process. (The Mighty From their Thrones, 155)

There’s so much more to say about the “process of submission and powerlessness” in the cross which Walsh describes. The powerless God who says to power:

Alas, alas, great city,

wearing fine linen, purple and scarlet,

adorned [in] gold, precious stones, and pearls.

In one hour this great wealth has been ruined.

(Rev 18:16-17)

This, more than anything, is the essential mystery of faith American Christianity has balked at and betrayed. Exploring this will probably be the most important work I can do in future issues here.

For now, though, how might we perform this “process of the cross”? What if we acted like the spectacle didn’t have the power it insists on having? What if we starved it of attention? Gave “lukewarm” takes? What if we answered with a kind of ignorance or neglect, or even better turned our attention to other, more urgent needs? The straits of our coworkers, the gentrification of our neighborhoods, whether our school districts are teaching the truth… Taking action might look an awful lot like a retreat away from those things everyone says we should be most outraged about.

And maybe, to our surprise, that would weaken the things that vex us. If publicity equals power and that power is going to a bad place, then the best approach is perhaps the paradoxical and certainly counter-intuitive gesture of the “Well duh.”

I’m grateful to do this work under the banner of unRival Network, a non-profit organization that accompanies peacebuilders to nurture hope, inspire collaboration, and overcome destructive rivalries in a nonviolent struggle for justpeace. This newsletter is part of unRival’s mission to expand its community of regular people seeking ever-better ways of being together:

If you value this work, and want to support it, please subscribe to this substack, and consider making a small donation to unRival to keep it going:

I still remember my lurid fascination with Plugged In’s scandalized review of AFI’s Sing the Sorrow (2003), which has since become one of my favorite punk-rock albums of all time. This might or might not be directly related to the breathless horror of the review.

Author

has some surprisingly encouraging thoughts on these issues in his book, The Forgotten Art of Being Ordinary. Check out his Substack, too:

Thanks for the mention Lyle!

I grew up in the LCMS and attended an LCMS private high school. During our cults and other religions class, our well respected teacher (among students and teachers) took up the banner against cultural darkness. Since this was the early 90s, D&D topped the danger list, but he lost my attention when he continued to spread the rumor that Anton LaVey sponsored Black Sabbath and appeared on their album artwork. I knew that not to be true. There has always been a subset of Christianity that pushed narratives into speculation and rumor. I never quite understood why. The Bible stands alone as testimony and nothing more is required to elevate the faith. There is no basis for antagonism.

I look forward to your future "non critiques" because it's a very difficult road to travel. The best I can discern is our efforts should simply be spent as the hands and feet of Jesus in service to the community.