James Cone and "Religion for Losers"

... And for Overcomers. The invitation of "The Cross & The Lynching Tree"

Two weeks ago, I invited you all to think with me as I processed some questions from a friend of mine, responding to some (admittedly out of context) passages from James Cone’s The Cross and the Lynching Tree:

Bonfires II: What is Possible with God?

Good Monday, everyone! First, a little housekeeping: exciting things are happening at unRival, and I’ll need to be on-deck for most of it. For the sake of managing my attention and keeping this Substack high-quality, I’ll be moving from a weekly to a twice-a-month schedule for the foreseeable future. That means you can expect to hear from me next on May …

This conversation matters to me not only because I see Cone’s work as emblematic of what a “religion for losers” should be, but also because my friend’s questions about his theology help clarify what’s at stake in doing theology together in the first place.1

Theological disagreements, even among lay people, are not like disagreements over whether Ted Lasso is overrated, or whether Taylor Swift is the greatest pop artist of all time. Because they involve our ultimate values, our theological conversations will also set the rudder for how we treat one another and how we try to shape the world around us. So when even frustrating questions are asked in good faith, we should do our best to “give an answer for the hope we have” (1 Pet 3:15).

Here again are the quotes from The Cross and the Lynching Tree that prompted the conversation, with what I think are the most provocative parts in bold:

The crowd's shout 'Crucify him!' (Mk 15:14) anticipated the white mob's shout 'Lynch him!' Jesus' agonizing final cry of abandonment from the cross, 'My God, my God, why have you forsaken me?' (Mk 15:34), was similar to the lynched victim Sam Hose's awful scream as he drew his last breath, 'Oh, my God! Oh, Jesus.' In each case it was a cruel, agonizing, and contemptible death…

The cross and the lynching tree interpret each other. Both were public spectacles, shameful events, instruments of punishment reserved for the most despised people in society. Any genuine theology and any genuine preaching of the Christian gospel must be measured against the test of the scandal of the cross and the lynching tree ... The gospel of Jesus is not a rational concept to be explained in a theory of salvation, but a story about God’s presence in Jesus’ solidarity with the oppressed, which led to his death on the cross. What is redemptive is the faith that God snatches victory out of defeat, life out of death, and hope out of despair.

To these claims, my friend replied,

What [does] Cone mean by the cross and the lynching tree interpret each other? How is that so? He suggests that the cross and the lynching tree are inextricably linked… Is it saying that Jesus’ death on the cross is really about solidarity with the oppressed rather than salvation? [Because] I would be opposed to interpreting, measuring, or testing the cross of Christ via the lens of a human experience, and not solely through Scripture and the prophecies that were fulfilled on the cross… [Jesus] became sin who knew no sin, so that we might become the righteousness of God [2 Cor 5:21]. He was not killed by an angry mob, but rather gave up his life…for us…rich or poor, the meek and godly, but also the ones who would perform executions and lynchings, and…all manner of grievous sins… It was a necessary spiritual condition that the punishment for our sins would be paid (penal substitutionary atonement).

As I said in my last post, even my friend’s questions have questions. And because these questions involve even deeper assumptions about how we read the Bible and how we understand what God is doing in history, any attempt to answer will lead to even more questions. But we have to start somewhere, and so I’ll start with my reader in mind: with the face-value questions that most easily scandalize and prevent evangelicals from engaging a thinker like Cone. I think it comes down to this:

By insisting that Jesus’ death on the cross is “about solidarity with the oppressed,” is Cone thereby also saying that Jesus’s death isn’t about salvation? If Christ does not go willingly to the cross as a substitute for us, taking a punishment we justly deserve, how can there be anything supernatural or saving about the cross at all? Doesn’t this reduce it to a kind of stage play in which God says an awful lot but doesn’t do very much? And if so, isn’t it a particularly lurid display of God’s preference for the poor over and against the rest of us not-so-poor?

I think these are entirely fair questions, which I also had when I first started reading Cone. I think the instinct to preserve the supernatural character of the Gospel story is a good one. It is “conservative” in the best sense of the word: it puzzles about how to preserve a timeless truth in a changing world that’s always facing new concerns and crises. Without the spiritual component of the atonement, without the cross’s role in God’s intentions for salvation, and without the universal relevance of that salvation for all people in all places at all times, Christianity comes apart at the seams.

Thankfully, the role of these things in Cone’s theology is fairly clear. To show this to my interlocutor and the rest of my readers, I’ll offer what I hope is a faithful summary of The Cross and the Lynching Tree (2011).

I want to sidestep the question of Cone’s orthodoxy for a moment and instead grant that he takes a certain kind of “mere Christianity” as a given. In fact, taking such theological foundations as given is essential to Cone’s project, because he is asking, from the same theological foundations as his white brothers and sisters in Christ, how an ostensibly “Christian nation” looked the other way for centuries while black image-bearers were dehumanized. “What does the cross in the Christian scriptures…have to say about these enduring atrocities [of racism and lynching]?” he asks (29). It’s a question to individual American believers as much as to theology as a whole: how did “proclaiming the cross of Christ” become a strategy for avoiding the questions of race-based discrimination and violence that shaped America’s identity, especially in the 19th and 20th Centuries?2

By assuming foundational theological agreement with his audience, Cone is also trying to show how, in the words of Howard Thurman, “the slave undertook the redemption of the religion that the master had profaned in his midst” (133-34). While Bible-quoting plantation owners spoke to their slaves about sin and the promise of salvation through obedience to their betters, black slaves were seeing a very different picture of Christ on the cross. They saw a God who not only forgave their sins and justified them by faith, but who also saw their immediate suffering and innocence. All people may be guilty of sin, but black people were routinely punished, tortured, and killed for things they did not do, just as Christ was, and so they entered into deeper intimacy with the “unmerited suffering” of the one who saved their souls (86). Jesus’ innocent sacrifice empowered black Christians to advocate for their own dignity. “The cross sustained them–not for suffering but in their resistance to it” (148).

This innocent Christ “became sin” so slave and slave owner alike might be saved. Cone affirms this: “Blacks and whites are bound together in Christ by their brutal and beautiful encounter in this land,” he writes. “We were made brothers and sisters by…the blood of the cross of Christ. No gulf between blacks and whites is too great to overcome, for our beauty is more enduring than our brutality” (165-66).

But Christ’s universal sacrifice, his “becoming sin,” also gave black Christians language for what was happening to them specifically: under the yokes of chattel slavery and Jim Crow, they were made to “become sin” all over again, necessary sacrifices for a pure (white) America. Cone asks us to learn from the ways the black experience understood salvation in this context, and how the suffering of one particular group points back to the universality of the cross, and forward to us again.

This is another point of contention raised by my friend: “I would be opposed to interpreting, measuring, or testing the cross of Christ via the lens of a human experience.” They are skeptical that human experience “adds” anything to the cross.

Cone agrees! “The lynching tree also needs the cross,” he writes, “without which it becomes simply an abomination. It is the cross that points in the direction of hope, the confidence that there is a dimension to life beyond the reach of the oppressor [Lk 2:4]” (162). Without the supernatural power of the cross, and without Christ’s making his cross a relevant symbol for all humanity, the lynching tree would have no meaning.

But Christ does refer himself to all humanity through this cross; “Crucifixion first and foremost is addressed to an audience,” writes New Testament scholar Paula Frederickson (quoted on p.31), and Christ’s audience is all of humanity down through history. Christ gestures on the cross to every suffering person, and also to every guilty oppressor. This universal gesture makes contextual theology possible: the story of the cross inserts itself not only into human history in the abstract, but into every story human beings tell about themselves. In this gesture, Cone sees a divine invitation to use the cross make sense of the lynching tree and to prophetically judge America.

Among his judgments, Cone criticizes the way America has “spiritualized” the cross, making it solely about our future destiny and not about the way our lives in the present. By reducing the gospel to a mere promise of life after death, Christian slaveholders made the Lord of the universe into an “opiate,” a drug to help their chattel “adjust to this world” of suffering (155). After the abolition of slavery, they still “claimed to be acting as [good] citizens and Christians” when they lynched blacks for being out after dark (159).

Cone calls the Christian gospel “God’s message of liberation in an unredeemed and tortured world” because it reveals and condemns such injustice; it is “more than a transcendent reality, more than ‘going to heaven when I die, to shout salvation as I fly.’” If Christ’s atonement for our sins supernaturally regenerates our hearts, then the gospel should change how we live and how we treat each other right now (155). We who hear the gospel and leave captives captive are without excuse.3

So when Cone writes that “any genuine theology and any genuine preaching of the Christian gospel must be measured against the test of the scandal of the cross and the lynching tree,” he isn’t challenging the cross. And he isn’t challenging the Gospel. He’s questioning the authenticity of a theology which holds its most important implications at arm’s length–a theology which forgets that it is the intended audience of the cross, called to action on account of how much it has been forgiven (Luke 7:47). “The transcendent and the immanent, heaven and earth, must be held together in critical, dialectical tension.” (156). The supernatural victory of the atonement and Christ’s earthly command that justice be done in his name go hand in hand.

There is no “either/or,” no “rather,” between Christ’s solidarity with the oppressed and Christ’s vicarious sacrifice on behalf of all people. Cone subtly notes that the cosmic seriousness of sin makes all people into victims; black people were victims of white violence, but white people also victimized themselves through their violence. They scarred their own hearts, built communities based on hate and cauterized souls. Cone does not discount the seriousness of divine wrath incurred by white Americans, and that it brought forth a real sort of suffering from which they need saving.4

Cone isn’t asking white people to see God on the side of oppressed blacks over and against whites; he relentlessly questions the “theological blindness” that leads whites to, like the prodigal son in the Gospel of Luke, abandon their own solidarity with God by forgetting their own needfulness: “As I see it, the lynching tree frees the cross from the false pieties of well-meaning Christians… The lynching tree reveals the true religious meaning of the cross for American Christians today. The cross needs the lynching tree to remind Americans of the reality of suffering–to keep the cross from becoming a symbol of abstract, sentimental piety. Before the spectacle of this cross we are called to more than contemplation and adoration” (161).

These are the first of my answers to my friend’s beautiful questions. The cross and the lynching tree are inextricably linked because white Americans, claiming to know better, echoed the crucifixion of Christ in their violence against black Americans. Jesus’ death on the cross was necessary for our salvation and the healing of our spiritual condition. That healing came through his solidarity with us as poor and oppressed, and by that solidarity even unto death, he demanded we liberate the poor and oppressed among us. No human experience can measure or test the cross of Christ… But the cross of Christ does enable us to prophetically interpret, measure, test and judge the theologies of our context and whether they are choking the Word of God in our midst.

Every answer is a necessary “both/and.” A fertile tension between the supernatural realities God enacts in history, the price paid on our behalf, and the earthly implications we are responsible for.

Does all this help to ease our sense of scandal over what Cone is saying? … Maybe. I hope it makes us more willing to listen, if we know we’re all starting from similar footing. But the implications go deeper, and we’re not done talking about them. It’s clear that Cone isn’t leading us towards a “balanced” atonement, in which substitution and liberation carry roughly equal weight.

And this is likely to be unsatisfying to some. It might still be unsatisfying to my friend, who writes: “[Christ] was not killed by an angry mob, but rather gave up his life for us.” I take this to mean that any theology which doesn’t foreground the sovereignty of Christ orchestrating his own crucifixion misses the point.

… But I think this is wrong.

I’d hazard that this is the only thing my friend is uncomplicatedly wrong about, but it is an oversight with tremendous theological consequences. It affects not only how we read Cone, but how we understand all our other theological priors. Our theology inflects our anthropology: what we believe about ourselves and our fellow humans affects how we treat each other. Thus Cone says all theology is ultimately political.

Christ gave up his life for us–rich or poor, meek and godly, executioners and lynchers… But we, the angry mob, lynched Christ. Scripture won’t let us around this fact: it is through but also despite our murder of God that God saves the world. If we cannot recognize and take responsibility for the human violence that placed Christ on the cross, our other relationships go askew as well.

Another both/and, but one that deserves as much time and attention as we can give to it. We’ll start scratching the surface of it in two more weeks.

I’m grateful to do this work under the banner of unRival Network, a non-profit organization that accompanies peacebuilders to nurture hope, inspire collaboration, and overcome destructive rivalries in a nonviolent struggle for justpeace. This newsletter is part of unRival’s mission to expand its community of regular people seeking ever-better ways of being together:

This Fall,

and I will be working with unRival to refresh the hearts of US-based Christian leaders buffeted by polarization but motivated by nonviolent theology and discipleship. We’re designing a safe space for doubt, wrestling, and healing together. A community for developing spiritual habits that protect us from isolation and burnout. If you value this work and want to support it or be part of it, please get in touch, and consider making a small donation to unRival:It also matters because two days ago—May 25—was the fourth anniversary of George Floyd’s murder. I'm light of that moment, all the questions discussed in this post have been revived with new vigor and urgency. We are confronted with the fact that we never finished—and are never finished—responding theologically to the problem of race. We need James Cone now as much as ever.

If the question of Cone’s orthodoxy hinges on his affirmation of Christ’s substitutionary atonement on behalf of humanity, that’s a mercifully easy question to answer: “The cross is the truth,” Cone says, approvingly citing Reinhold Niebuhr, “because God is hidden there in Jesus’ sacrificial, vicarious suffering” (36).

Cone does not belabor this point for his audience. He assumes they believe, like he does, that Jesus went to the cross as a sacrifice, and that his death supernaturally saves those who believe in him. A Methodist, Cone rooted himself in the Wesleyan branch of reformation Christianity, and among theologians John Wesley was one of the best at holding in productive tension Scripture’s many descriptions of how Christ redeems humanity on the cross: “The voluntary passion of our Lord appeased the Father’s wrath,” he writes, “obtained pardon and acceptance for us, and consequently, dissolved the dominion and power which Satan had over us through our sins.” Rather than prove this position or justify it throughout his text, Cone assumes this is more or less the position from which his audience will engage as well. It’s worth unpacking in more detail in later posts.

Here, again, we see Cone’s Wesleyan formation showing itself, as the regeneration of the soul is a major (if sometimes controversial) characteristic of Methodist theology.

“What happened to blacks also happened to whites,” Cone writes, in a passage that’s quite scandalous on the face of it. “When whites lynched blacks, they were literally and symbolically lynching themselves–their sons, daughters, cousins, mothers and fathers, and a host of other relatives” (165). Cone’s symbolic sense here is easy enough to understand, but he does mean this literally as well: racial mixing was a terrible taboo in Jim Crow America, and a disproportionate number of lynchings followed accusations of rape. But despite one-drop rules and other efforts, whites and blacks did love each other and have children together, and white vigilantes would inevitably–if unknowingly–murder their own kin.

Still, Cone’s gesture to include white people as victims of Jim Crow violence is staggering. Read uncharitably, it diminishes black suffering by “both-sides-ing” the conversation. But read with Cone’s preacher’s heart in mind, one sees a profound gesture of solidarity that can only be made by taking sin seriously as the “enemy” Christ defeats.

Another author who understands whites as “victims” of racial violence in subtle but meaningful ways in Tananarive Due. In her novel The Reformatory, physical places can become so saturated with memories of hate and violence that they start affecting those who live there, black and white alike. The “sins of the fathers” diminish the moral freedoms of their children. In this sense, Due is able to portray whites as “slaves” to their own history of violence, themselves needy of redemption and liberation, without equivocating between black and white experiences. A must-read.

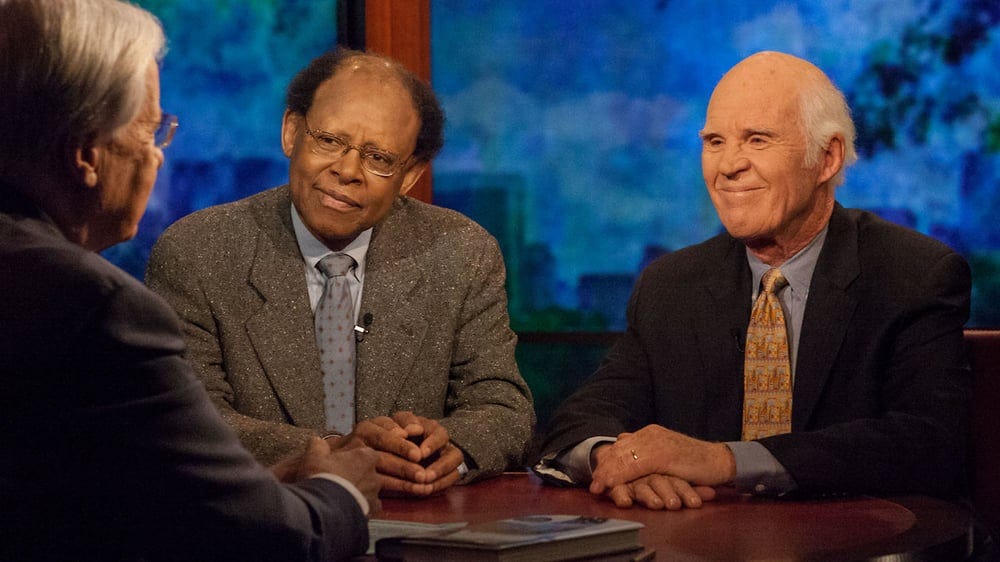

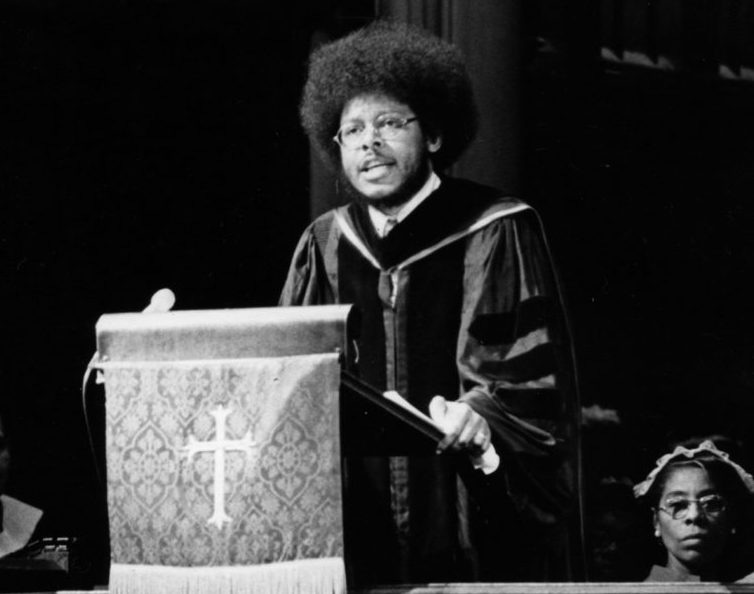

Thanks for this, it gets at the core of the issues very well. Cone gave the Paddock Lectures at General Theological Seminary, where I was library director, while he was finishing The Cross and the Lynching Tree. I'd worked at Union & knew him a bit, but it was in those lectures that I recognized the positive orthodoxy of Cone's theology--given the intensity of the subject, I remember those lectures as almost irenic, i.e. that we were in this project together.

So, several years later, when I was serving every Sunday at a Black parish in the south Bronx, his words came to mind for my first Palm Sunday there. Here's the sermon I preached. I think it's pretty orthodox, at least as orthodox as one can be while facing the facts of the crucifixion.

https://drewkadel.wordpress.com/2015/03/28/crucify-him/

Thank you for this article. It is impossible to not make the connection between Cone's "Cross and The Lynching Tree," and his statement in "A Black Theology of Liberation" regarding forgiveness. He said, and I dare to paraphrase, that forgiveness is a gift from below. It comes from the oppressed without the pressure of the oppressor. It must be given freely, for we cannot add another burden to the oppressed through forgiveness.