Happy Easter Monday, all!

In my last post, I threw in my two cents about Christianity “dying” in America. Appropriate to Holy Week, I gave what I hope was an honest, lucid opinion of what that “death” really means and how we’re likely to experience it. I also set out a perhaps fuzzy vision of the spirituality that I think will sustain us through this “death” and into the “something else” beyond it—namely, the resurrection many of us celebrated yesterday.

I ended with a quote from the Swiss theologian Hans Urs von Balthasar in his 1988 meditation on Holy Saturday. The love which “descends into hell,” he says, is at once an opportunity to “give ourselves unreservedly into the hands of God” and also, miraculously, an “earning of grace for others,” enabling them to “choose love as their innermost disposition.”

It was a pretty mystical note to end on, but deliberately so. Though I intend to spend most of my time talking about theology, culture, and current events in these pages, we are ultimately thinking through the spirituality that will sustain us into the future. This will always require making room for a mystical element that gets passed back and forth over our concrete, everyday experiences, allowing them to mean something more. That is where Christ meets us, always beckoning us back down into our very human lives, into the things that anger and vex us, teaching us to accept the needfulness that is the loam of “abundant life.”

Balthasar frames “death” as an essential part of this experience. At least, we can embrace death’s role in the work of love and transformation because of how Christ has already transformed it. No longer the final act, the final shame, death and the preparation for it leads us to “abandon our egoism” and our “wanting to be for oneself,” to “choose love as our innermost disposition.”

But what does it look like to “choose love as our innermost disposition”? How do we recognize it in others? What models might we look to for that “descending” love we ought to imitate?

We might think of saints or spiritual leaders, but lately our “heroes of the faith” appear to be falling in record numbers, discredited for hypocrisy and abuse. These scandals and the lack of accountability around them are some of the biggest reasons people leave communities of faith in droves. If Easter takes the sting out of shame and death, these scandals redouble it through power and manipulation. They destroy any credibility in the counter-intuitive form of Christian love.

If we want to find an imitable spirituality, we must look for it in inconspicuous places—away from the pomp and power that so many religious leaders have courted and enjoyed. But that leaves us asking again: who can we look to now, in a world reeling from our failure to show the love Balthasar describes?

Each of us is going to start that search in different places, and I’m planning to fill a lot of pages with examples—folks like James Cone, Ivan Illich, Rene Girard, and others who inspire me. You might find those models in folks who aren’t even Christian.

For today, though, I want to start closer to home—in the shoes of a parent whose teenager plans to have friends over for dinner.

Maybe you already are the parent of a teenager, and I’m drumming up some spectrum of pride and affection, quiet caution, and muscle-spasming anxiety. If your kid is anything like I was, they’re also letting you know about their plans while said friends are already on the way over. If you still have your wits about you, maybe you’re shoving the little social networker out into the backyard with coupons, pizza money, and an earful about how considerate a simple “heads up” can be.

As their kids’ friends are en route, I don't know that many parents think, “Oh hey, this sounds like a great way for me to spend my evening.”

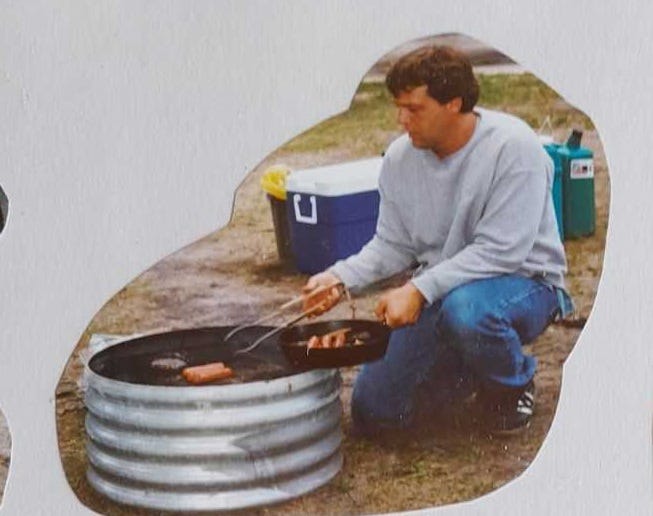

My father never said so, either. He’d disappear while six 18-and-19-year-olds demolished their dinner. But then he’d return through the back door and announce that he’d built a fire if anyone wanted to come and enjoy it. Which we did. Frazzled from summer jobs, one week away from going back to college, there wasn’t a better way to enjoy a dark August night.

And as we brought the cooler out, found weird sticks and ringed around the pit, Dad stayed. As was his right, it was his house, his yard, but he didn’t just make a space for us and then leave it. The vibe I always got was that he’d made a space for him, the simple pleasure of which he trusted, and he invited us to enjoy it with him.

Then, he’d ask questions.

Growing up as a pastor’s kid, I was already pretty used to Dad taking a deep interest in my life–the kind of interest that asks, “How are you doing really?” and, “How might you make that better tomorrow?” Dad is skilled at asking questions that he’s really trying to get you to ask yourself. And while I got wise to that pretty quickly and even resented it for a spell, I also realized that, at those bonfires, he asked my friends questions about their inner lives that probably not even their parents asked–or didn’t know how to.

Which is why they stuck around. Why they answered without hedging. You might even call it naïve of them to open up to a friend’s father. Each of them was more or less raised to believe that this is how you talked with a pastor, but few pastors really gave them the opportunity–or else they abused the trust. In hindsight, their willingness to talk to Dad about their doubts and moral chafing was nothing short of remarkable. I don’t know that any of them would (or should) be so open today.

A lot of it was in how Dad responded. When they turned the questions back on him–the deep, abstract questions about heaven and hell, sin and evil, doubt and disobedience–he was ready. Chuffed, even. This was what he wanted. Not the opening to deliver confident sermons on doctrine, but his chance to ask his two favorite questions: “What do you think?” And after receiving a few answers: “That could be, but what if it’s more like this?”

My father is seminary-trained, well-read, deeply philosophical about his faith, and a tried-by-fire youth pastor, but he has always been starved for intellectual connection. I’ve got a memory of being maybe 11 years old, and he’s unpacking the Kalam cosmological argument for the existence of God to me while we’ve got our feet in Lake Huron trying to hook just one bluegill before the sun goes down. This man built these bonfires, hoping to ease the hearts of his son’s teenage friends. To create an oasis for questions in a world that saw us on the cusp of adulthood and really wanted to give us its own answers for how we ought to be.

The magic for him wasn’t in teaching us what he knew or getting us to the “orthodox” answers. Certainly, he believed there were answers, right and wrong ones, truths and lies, but the existence of a right answer did not remove its veil of mystery or the arduousness of arriving at it. Of finally picking its lock and throwing its door open, only to realize the answer was bigger than the question.

That’s what I learned around those bonfires. It was about asking hard things with people you loved and what you learned about each other in the process. It was about the satisfaction of plumbing a deep, messy truth instead of being satisfied with just a little, clean, pragmatic cut of it. It was about leaving that fire feeling like the world was bigger than when you arrived. And it was about trusting a bunch of college kids with something far more wonderful, terrible, and high-stakes than a car or a credit card: their own becoming. Their self-transcendence.

About a year ago, at the edge of another bonfire, I was at a particularly bitter trough in my religious life. I was starting to wrestle with the same questions of Christianity’s “death” as I raised in my last post, and my friend

sensed anger was getting the better of me. He advised, “You need to find a place of joy you can lead from.” At the moment, I had no idea what that might be.Then, over a cigar, I told him why I was still a Christian. Why faith in a supernatural redemption shaped like a criminal execution keeps its nails in me and won’t let go. I told him about Dad and his bonfires. About the beautiful patience of a man who brought me and my friends to the edges of our hearts, convictions, and assumptions. He had no idea whether our leaping off that cliff would lead us closer to or further away from the truth he felt so confident in… But he invited us to leap anyway.

“That’s it,” Joel said–all the more authoritative thanks to a cloud of smoke and a smoldering ember between his knuckles. “That’s your joy. You’ve got to build your bonfire, man.”

You’re reading this because I decided he was right. That the best thing I can do in this angry, anxious world is to build a space of peace in my own heart and see who shows up to it. I’ve got credentials that might inspire a little confidence on these topics: a Ph.D. in religion and literature, peer-reviewed competency in theology, the arts, and political philosophy. But the world is about a billion times wider than my expertise, and right now, that expertise is better set to work asking new questions rather than providing new answers.

What I hope is more valuable, in the end, is my concern: my sense that things are getting harder and that it’s not going to change any time soon. And with that, my deepening conviction that we need each other, need our neighbors, need to really know how deeply we’re in this together and have plans for doing life together if we want to be ready for whatever is on the horizon for ourselves and our nations. We need backyard spaces where that can happen, even in digital landscapes, which seem less and less hospitable to such things.

Still, I’m here to try. For logs, I’ve got a few things I can’t do without: my religion. My passion for justice. My conviction that the whole cosmos is shaped by a desire for peace that passes understanding in and between all people. For kindling, where my Dad used newspapers, I’m using… Well, the news. The rapid-fire events constantly unfolding that none of us are really qualified to solve, and yet we can’t ignore them, either. Things like,

How does conspiracy thinking around Kate Middleton or the Baltimore bridge tragedy reflect our disconnection from the sacred and distract us from seeing deeper human needs?

What does Beyonce’s new album teach us about the long work of justice and of never ceding symbols of liberty to those who would misuse them?

As our systems become more transparently corrupt, how do communities cultivate a patient faith in justice—or a properly impatient civil disobedience over the same?

Finally, there’s the pit. The little divot of attention and concentration that makes something like this possible and, hopefully, different. A place for gathering your neighbors with cold drinks, carefully-meted quiet, and a tone of voice that lets them know you want to chew on some pretty ultimate things. That you want to have some opinions and make some judgments. That you’d like to be patiently wrong about it all, together, and keep being wrong until the joys of ever-better judgments arise. Because none of us knows what we’re doing, and we’d all like to know a little better.

I hope you find this at the bonfire I’m trying to stoke. And if it catches, or smolders, or erupts, or sputters in the wind as I’m sure it will at stages—or if I turn out to be witheringly wrong about something and need to dump the ash of what I’ve said and start us over—then I hope you’ll feel we’re still getting somewhere together. Being wrong needn’t mean the end of the world if we trust each other with our becoming.

And we can. That is also one of the small miracles of Easter.

I’m grateful to do this work under the banner of unRival Network, a non-profit organization that accompanies peacebuilders to nurture hope, inspire collaboration, and overcome destructive rivalries in a nonviolent struggle for justpeace. This newsletter is part of unRival’s mission to expand its community of regular people seeking ever-better ways of being together:

If you value this work, and want to support it, please subscribe to this substack, and consider making a small donation to unRival to keep it going: