Over in the Artisans of Peace program,

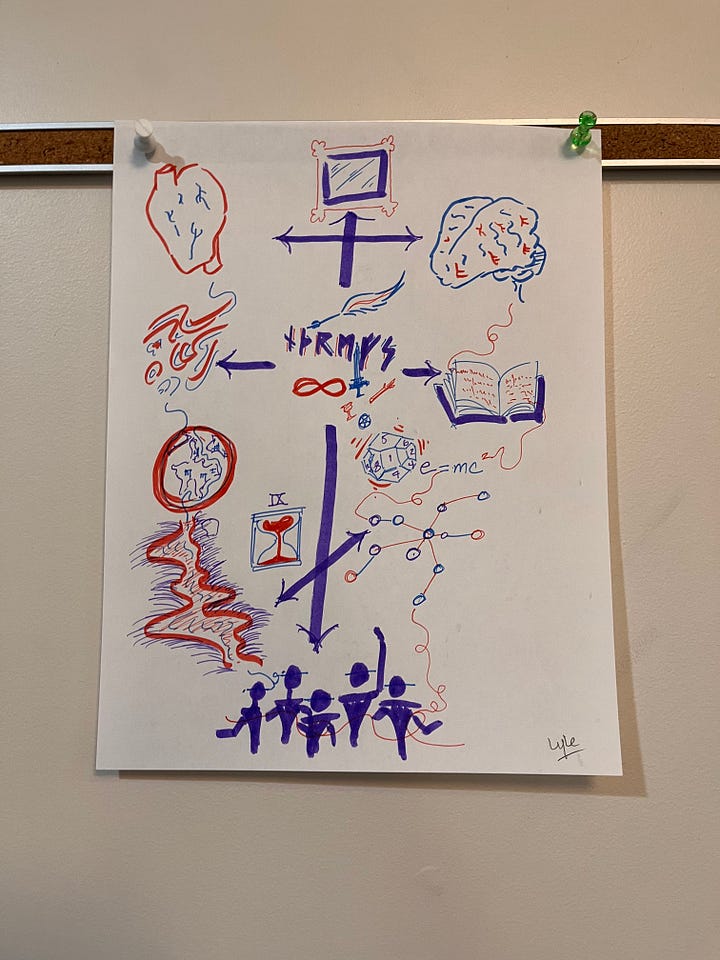

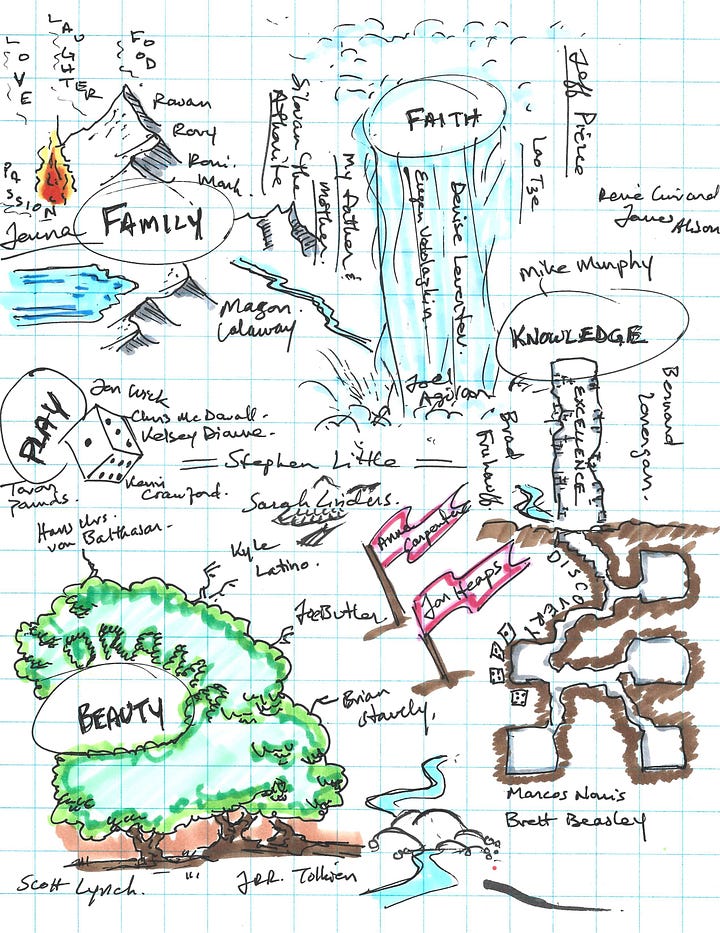

and I are walking participants through a process we call a “Desire Map.” It’s pretty much what it sounds like: write your desires on a piece of paper. Embellish them with colors and images. Associate those desires with specific moments and milestones in your life. Crucially, identify who was around when that desire first entered your heart. Who inspired you? Who supported you? Who, perhaps, got in your way?

The exercise has been illuminating for everyone. Some people are seeing surprising continuities between the longings they have now, and the desires they had when they were younger. Others newly appreciate the power of community in forming desires, in bringing them to fruition—or, tragically, frustrating them. A few wise souls feel uncomfortable that the exercise doesn’t ask them to discern between “good” and “bad” desires, and realizing that such distinctions are more complex than they first supposed. Still others are realizing they’ve never desired in these ways at all: “I’ve spent so much of my time pleasing other people,” we’ve heard more than once, “that I don’t think I ever learned how to want anything for myself.”

I think all of us have had moments where “What do you want?” turned out to be a really hard question to answer. I don’t think many of us have felt it be painful. We don’t often feel that asking what we want somehow strains an under-used muscle, that we need to somehow become better at wanting before we really answer the question.

I’m feeling all this myself because I’m right in there with everyone else in this cohort. Asking this question has more or less been part of my job description at unRival, as a co-designer and now facilitator of the Artisans of Peace program: to ask, and be asked in return, “What do you want?” in the name of peace and justice.

Recently, my support system at unRival—which also gave me time and license to write here at Religion for Losers—has gone through some major changes. It’s not going away, but we’re rethinking what it looks like; the changes are big, and I’m bigly implicated (and grateful to be part of the conversations).

When it comes to Substack, specifically, I probably can’t keep doing things the way I’ve been doing them. I don’t publish even half as often as some people on this platform, but the time and energy I have spent here thus far were graciously funded by unRival and I probably wouldn’t have had that time or energy otherwise. I have to be honest with myself about what my resources look like without that support, and whether this is a place I want to continue investing my limited reserves.

But even asking that question also frees me up to allocate those resources differently, to try new things, and to honor the roughly 500 of you who have been kind and generous enough to sign up and hear from me regularly. I’m not asking the question just for myself here, but it is still mine to mull over and own: “What do I want?” And I need to fully respect how hard that question is–and perhaps ought be–to answer.

I started Religion for Losers with a question: “Is Christianity dying in America?” I wanted to use this space to explore what Christianity might do with its legacy and institutions in shambles. To anticipate what it might be like to suffer persecution at the hands of those who also call themselves Christians. And I wanted to do that in ways that didn’t just emphasize the stakes of the present moment but really kept eyes forward on the future, on the persistent Easter doing we’d be called to.

In many ways I’ve stayed true to my original intentions; in others, I’ve deviated from it. Mostly by falling into the temptation of having a “hot take,” of offering an angle on the news of the day rather than something a little more oblique, a little more “off to the side,” a little disconnected from the information cycle and so, perhaps, more insightful and “resurrection-minded” on account of it. Something more heuristic or maieutic, based on what I loved rather than on what was driving me nuts. Socrates might have driven other people nuts by constantly asking what “justice” was, but no one can doubt that he asked from a deeply passionate, even enamored place.

Writing this publication has been a months-long lesson in how hard it is to sustain a tone and vision like that, even when you’re trying to do it on purpose.

Part of the problem, honestly, has been this platform itself. The internet, in its current incarnation—a sea of likes, reposts, and performance metrics constantly thrust into your face—seems patently designed to aggravate my competitive need to be noticed and affirmed. Substack’s Notes feature, along with its aggressive new focus on keeping things tethered to its app, have re-burdened me with some of the same furies I thought I left behind when I permanently logged out of TwXtter a few months ago. Some people are genuinely energized by “putting themselves out there” in these ways; I am not one of them. Learning what a platform like Substack “wants” is a problem that’s like candy to my brain, down to the fact that it makes me sick by being unsolvable. You think you’ve got your tongue wrapped around the tantalizing layers of a jawbreaker only to realize it’s Sisyphus’s rock. That this feeling isn't unique to me is a small but genuine comfort, though it doesn’t make the waves easier to ride as I try, week after week, to say something true—only to be disastrously distracted by emails (or a lack of them) notifying me that someone has “Liked” my most recent post.1

To be quite honest, like many of my fellow sojourners in Artisans of Peace, I’m just now getting my head around the idea that it isn’t wrong for me to believe, on my own judgment, that I have something good and excellent worth putting out into the world. It is not wrong to want that goodness proven out in the course of conversations, growing readerships, maybe even a buck or ten that can help me tell myself that, yes, I did something good, and someone out there wants to help sustain me in my ability to do good. It’s not even wrong, I’d hazard, to stop at the simple, smelly desire of wanting to be paid for doing something I love. It’s not wrong to want to feel significant.2

But while not wrong, I’m learning these desires can be unwieldy. They’re earnest, valid, even innocent on their own, but awkward when bundled together. It's work to carry them around. Like with my squats at the gym, my form could use some work. I am still not very good, yet, at wanting well.

Part of that is because, while the desire for excellence and the desire for validation often go hand-in-hand, they also tend to work at cross purposes. One can desire validation and recognition as evidence that one is achieving excellence in their craft, wisdom in their thought, but too often—as

convictingly reminds us—ambition demands excellence as a blood sacrifice. In the pursuit of wisdom, the Bhagavad Gita gets it exactly right: “Thine right is to the work, and not to the fruits thereof. Let not the fruit of action be your motive, nor let your attachment be to inaction” (2:47). Excellence works quietly, thoroughly, persistently, hoping for—but never able to guarantee—the validation and recognition deserved by a job well done. In fact, it works in spite of this lack of a guarantee; it makes peace with the lies of meritocracy and defies it.Ambition, meanwhile, in the name of validation and recognition, eats quiet and thoroughness for lunch. And yet the internet, Substack included, seems insistent on telling we who write and we who read that there is no contradiction here.3

For me, the increasingly bombastic emphasis on followers and metrics has gotten in my way of actually loving the work.4 It’s rankled me with reminders of how recognition, validation, and “success” are ultimately arbitrary, and of how deeply dissociated the longed-for “fruits” are from the work. For someone like me, that dissonance is actually searingly painful sometimes. It makes the work a hundred times harder and kills the desire to do it. It threatens in me the “needful” spirituality (modeled so beautifully by folks like

and Joel Aguilar) that upends our priorities and, from there, makes genuine excellence possible.Beautiful as the Gita is, I prefer the way Fr. JPM Walsh puts it: that when we accept the radical, divinely-ordained disproportion between our efforts and their results, we can either rail against the perceived arbitrariness or lean into the liberation of gratuity:

“Gratuity…simply bypasses a sense of earning and proportion and entitlement and deserving, as being beside the point. Gratuity can take a couple of different forms. One is playfulness. If you go about some project or activity in a spirit of playfulness, there is no further agenda at stake. You can invest vast amounts of effort and be wholly caught up in it, but all that matters is the love of it. Even if you are not that good a pianist…you [can] fall in love with it. It will be hard work but it will be a joy… [T]he liberating joy of working at something, free of the self-regarding compulsion to prove oneself.” (The Mighty From Their Thrones, 122-23)

This might sound like I’m winding up to leave Substack, or at least go on a long hiatus. I’m actually not, the above wall of text notwithstanding. At least, not yet. I’m definitely open to either of those scenarios. I’m certainly not going to hold myself to the same standards of strain and consistency as I have been, at least not for a while (though of course I remain committed to excellence). I'm going to keep testing my relationship with this space and see if I can make it properly mine—or not.

And I'm going to keep asking what I want. Right now, what I want is to see my daughter through the second half of her surgery recovery. I want to help my wife figure out why her stomach keeps bothering her, so we can stand together against the terror that is our son’s being four. I want to make myself more available to my church and to my fellow Artisans of Peace, including several of whom I’ve met here; I want to be a more attentive steward of those relationships.

Above all, I want to keep looking for ways to reclaim the Gospel of Jesus Christ in my context as truly good news for the losers, the poor and the cast-offs, which all of us are. I want to do that more through projects rather than pot-shots.5

And, in the interstices, I want to write more stories. (Fantasy stories, dammit; stories with veiled gods and haunted oceans and dragons. I don’t think I’ll ever be able to say half of what I really believe if I can’t put dragons in it.)6

I also think I want to focus my efforts more on traditional media and publishing. I think I’m better built for it. I’ve an abiding respect for gatekeepers, I prefer editorial back-and-forth to reliance on my own eye, and honestly I think I’m more emotionally suited to rhythmic waves of rejection letters than I am to the athazagoraphobic conditions of social media.

As for this space, I plan to use it more as a way to maintain momentum on these other things. Mostly as a way to keep myself accountable to all the reading that must necessarily fuel the projects I have in mind. I plan to post fewer carefully-wrought essays in favor of notes, reflections, questions and close readings. More bounded things. Which means I might, ironically, write more on here. You might even start seeing something from me every week, who knows.

The first such thing I plan to post—on the heels of many conversations with my wife urging me to get back in touch with my values and with things I love—is a read-through of Hans Urs von Balthasar’s Mysterium Paschale. If any text serves as a milestone for my values and beliefs, for what I mean when I call Christianity a “religion for losers,” this is the text. I’m looking forward to devouring it anew. To reminding myself of what it felt like to have everything I believed seismically shifting under me about 10 years ago–and for Christ to start making good on his promise, at least in me, that he is “making all things new” (Rev 21:5).

I think it’ll be a fun ride. I hope you think so, too.

Thank you for reading.

All Good Things.

A potentially revealing story: when I was in preschool, I had a rather obnoxious habit of answering all the teachers’ questions. One day, I raised my hand, and the poor teacher passed me over looking to give someone else a turn. Straining, slightly panicked, fearing I’d done something wrong, I whispered to my best friend–who was quite a bit bigger than me– “Why won’t the teacher call on me?” He thought about this for a second, then said, “I don’t know, but I’ll make sure she doesn’t.” And then, he sat on me.

I can think of no better analogy for what my experience with the creative life has felt like. And no better candidate for a root reason as to why I go to therapy.

Like absolutely everyone else does, too. This isn’t lost on me.

Cal Newport’s book Digital Minimalism has greatly influenced my thinking here. At some point I should collect my thoughts on how. I know my mom-in-law is still waiting for that particular write-up.

A love I am, to my great delight, rediscovering even as I sit and draft this on a full-screened Google Doc.

You're asking great questions, Lyle! Thank you very much for the shout out.

A great deal of my desire for writing comes from a place of holding thoughts in my mind, mulling over them continually and producing self-reflections that help me advance notions--it's like world building. I have contemplated stopping writing but to be honest, I like who I am when I'm trudging through ideas and trying to make them make sense, it feels more like me then when I'm doing almost anything else. As a result I find that when I'm not sharing this side of me and talking about it with other people, a part of me loses weight and I feel ideologically weaker.

All of this to say that I'm probably not going anywhere either.